- Home

- Michael Murphy

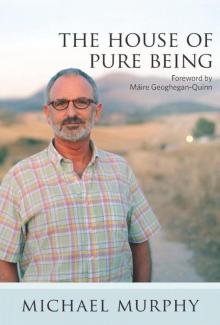

The House of Pure Being

The House of Pure Being Read online

The House of Pure Being

Michael Murphy

Foreword by Máire Geoghegan-Quinn

‘Aha, so he is the one who is meditating me. He has a dream, and I am it.’

Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections

‘But that kind man, that teacher, lover, friend, who remained indistinct, would be generous with words; she imagined their life together as a long conversation, equally shared.’

Anita Brookner, Fraud

‘The Jews, Ravelstein and Herbst thought, following the line laid down by their teacher Davarr, were historically witnesses to the absence of redemption.’

Saul Bellow, Ravelstein

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Foreword by Máire Geoghegan-Quinn

Part One: My Mother

Part Two: Live Big Young Man

Part Three: The Silence…

Part Four: Hanging from the Balcony by One Hand

Part Five: On Writing …

Part Six: The Man in the Mirror …

Part Seven: Terry’s Mother

Part Eight: That Dingle Day

Part Nine: Anna

Part Ten: Conor

Part Eleven: Helen

Part Twelve: You Could Make an Olive Dance

Part Thirteen: Aengus

Part Fourteen: A Poem for Terry

www.michaelmurphyauthor.com

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

by Máire Geoghegan-Quinn

‘Comhgháirdeachas ó chroí. I cried. I got very angry. I laughed out loud. What a wonderful story beautifully told with nothing held back. I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed reading it.’

That was my letter of congratulations to Michael Murphy after I’d read his memoir, At Five in the Afternoon. I meant it. And I suspect I assumed that it would stand alone, since it centred on what prostate cancer did to his life and his perception of his life. Such an experience, dragging a writer face-to-face with death, necessarily gives their work a unique shining harshness.

When he asked me to write a foreword for his sequel, The House of Pure Being, one of the reasons he gave for contacting me in Brussels was that when I had been Minister for Justice in Ireland in 1993, I introduced the Bill that decriminalised homosexuality. He told me that this was an act which had set him free.

I agreed without any hesitation to write some introductory words, and then wondered: what could be covered in a second book which would not be overshadowed and rendered trivial by the absence of a life-challenge to match the threat of death? Too many second books are little more than evocative shadows of the first, exemplifying Robert Frost’s shrugging comment: ‘In three words I can sum up everything I’ve learned about life: it goes on.’

In a sense, Michael’s second volume of reflections and memoir deals with precisely that: the progression of those we met in his first book. Or, in some cases, their failure to progress, most shockingly demonstrated in his account of family members who set an icy silence around the revelations within his first book. That silence invited the kind of surrendered retreat and matching silence often characterised, in the anti-massacred words of our parents, as demonstrating ‘common decency’. This book picks apart the concealments, the collusion and the coercion implicit in many of our notions of common decency. That doesn’t make it easy reading. But then, anyone who read Michael’s first book knows that he is neither an entertainer nor a panderer. To reverse a current cliché: you get much more than what it says on the tin, whether you like it or not, because this is not a man passively examining the shadows on the wall of his life’s cage. This is a man engaging with the cruelties of his past with a fury to which he had no access, back then. This is a man baulking, in what he describes as the evening of his life, at events, actions and hurts absorbed in silence at the time. This is a man at one with a writer I know he loves, Federico García Lorca, who held that an artist is always an anarchist, in the best sense of anarchy.

‘He must heed only the call that arises within him from three strong voices,’ Lorca said. ‘The voice of death, with all its foreboding. The voice of love. And the voice of art.’

Those three strong voices unite the varied writings within this new volume. The voice of death speaks, not only to Michael’s own experience with cancer, but through the dying of Aengus Fanning, former editor of the Sunday Independent, whose conversations with Michael, with their long, companionable silences, establish a side to Aengus that will be new to many who believed they knew him well.

The voice of love sings softly throughout the book. Love of friends, especially when their lives and happiness are unravelling. Love of place and time and the capacity to work. Love, above all, of Terry O’Sullivan, Michael’s partner, whom he met when, a quarter of a century ago, making a documentary about the Rutland Centre, where Terry worked.

The portrait of Terry manages to be affectionate and awestruck, culminating in the simple honesty of the poem he wrote as a Civil Partnership gift, the epithalamion: ‘… once upon a time on a Dublin midsummer’s day, I always loved you.’

What makes Michael Murphy singular as a writer is his ability to recreate an emotive scene or event, right down to the feel of the wind on his skin or the movement of a curtain against an open window. That ability is based on an almost obsessive acuity of recall, which hammers home a truth none of us needed to understand before Alzheimer’s Disease came to live in each of our families: that without memory, we are nothing.

This is a major theme throughout the book, painfully memorable in Michael’s account of a meeting with his elderly mother, where she struggles to tell him something she knows to be important, but which will not form words in her mouth.

‘My mother is ninety-three years old, and she dwells now in a house of pure being,’ Michael writes. ‘She has only the present tense, because she forgets what is past, and I’d come to believe she no longer has any idea of the future.’

Terry’s mother, too, reaches from beyond death to touch the lives of the two men, and of another who was forced to live a motherless life because of the constricting expectations in the year that he was born.

Michael’s poetry appears at different points within the prose of this volume. And, although the extract which follows was not written about himself, it may well reflect the experience of many readers as they finish this startling and beautiful book.

You will gladden with a smile or with a glance

When people feel your presence in the wonder of beautiful words

Lingering in a room like your fragrance

The blown petals falling to earth like prayers

Whispering over and over that I have always loved you

That I have loved you, too

Máire Geoghegan-Quinn,

European Commissioner for Research, Innovation and Science

Part One

My Mother

‘Imagine!’

That’s what my mother used to say. ‘Imagine, just imagine …’ It was her favourite exclamation of surprise at something suddenly made visible, a version of ‘fancy that!’ which she’d made her own. She would picture mentally what wasn’t present, what she hadn’t experienced, and speak about it, clothe it in words, as once she deftly fitted her eldest boy with upstretched arms into an overcoat. She was filled with wonder and delight at the miracle of creation which happened seemingly without her participation, but which nevertheless had somehow involved her: ‘Well, imagine that …’ she’d say. Today, as I write in my study in Spain, I can see her come out of the kitchen and walk diffidently down the hall, because she’s never been in La Mair

ena. Her ghost calls out to me: ‘Imagine!’ The invitation is a personal one from a mother to her son to join her in telling a story, and make an emotional connection with her in setting forth in words a fantasy which is unrestricted by reality, and write a fiction that comes flying out of the air from nowhere: ‘Imagine!’

The contract requires that I bear her in mind. So here I am on top of a mountain at four o’clock in the morning, with the lights of Fuengirola glittering like the brightest stars down below me in the darkness, my mother’s mouthpiece in this dual endeavour, giving voice to a narrative that has known the two of us over the years, and that has also shaped both of our lives, as we strolled around the Mall in Castlebar in Mayo, playing within the protective pathways of its gentle and nudging words, which set safe limits to our known world. Unlike Helen and Anna, those stylishly beautiful women who are my friends in Spain, my mother is an unlikely muse, but I feel safe under the protection of her azure cloak, her cobija, which now covers the vast, velvet belly of the sky with softness, pregnant with the possibilities of new life, because I know she has the knowledge that’s expressed in memory, best practice, and above all, the miracle of the human voice.

‘Imagine …’ she says.

‘… that there was once …’ I whisper back, continuing on her story as she strokes the side of my face with her finger, marvelling at the softness of my beard. And I see the sun begin to shine out strongly from her clear, blue eyes.

‘Michael,’ she calls, ‘I have something to say.’

‘What is it, Mum?’ as I move even closer to her. She’s examining my face intently, and her eyes suddenly fill with tears.

‘I don’t know what comes next …’ she says.

I am thunderstruck. ‘I know that, Mum.’ And I take hold of both of her hands. We remain held that way in the silence, looking at each other, and then the clouds arrive again and darken the sunlight, and my mother leans back into her chair, and I let go of her hands. I realise that I’ve sunk to my knees beside her.

My mother has gifted to me the awareness that she’s lost, that she’s without her ability to imagine. I can understand from the outside what a fearful tragedy that is. A fatal flaw in the workings of the brain has led to her downfall, and I grieve with her. But there’s also something that has been left unsaid in the dialogue between us, and there are still many possibilities within that gap. I shall continue to visit with her in the nursing home until she’s able to say it, or at least until such time as she enters the family home on the Mall in Castlebar for the last time, and closes the hall door in my face forever. Then, from the retrospection granted by that arbitrary end point, everything will have been said from her point of view, and she’ll have made her statement.

In the meantime, I shall try to put into words what she hasn’t yet said, because in itself it must be of the greatest importance, given my mother’s great age, and the wisdom of the personality that she’s earned for herself down through the years. It’ll be what the French call an aperçu, an insight, a summation in a few words, a recapitulation of the main chapters of her life. Perhaps it’s one of the reasons why I’ve written my second book, to give her voice in saying what has become unsayable, what’s impossible and unknowable. The disclosure will have the quality of a supernatural revelation, because it will be the truth.

Yesterday, I was reading the publisher’s blurb about my first book on his website, and saw that I was described there as ‘a soothsayer’, a person who tells or speaks the truth. The word also has overtones of being a prophet or prognosticator: one who is robed in foreknowledge of the future. Certainly, that’s the direction in which my mother has also pointed me through her being speechless. The words of her first sentence, ‘I have something to say’, were ordered by the future anticipation of the words to come in her second sentence. She wants me to articulate some imagined future state of conclusion. It’s a completion which I doubt can ever be achieved. Steve, my publisher, had brought forward his conclusion from my writing. Now I too was in the position of a reader looking over his shoulder. I saw myself through his eyes, and to my surprise, the effect on me was alienating. It split me in two. I was looking at myself in a looking-glass, except that the judgment Steve had delivered caused me to switch places, so that I was the insubstantial reflection confined within the singular word he had chosen, from whence I was looking back at myself, helplessly in thrall to what he had in mind.

I can remember coming around the back way from where I lived with my grandmother, and peering in the kitchen window at my brother and my mother and father, who were laughing and joking around the dining table. At that moment, I felt I was the stranger looking on, extraneous to the family’s enjoyment. And when they all turned their heads to look at me, I reddened under the sting of their gaze, ashamed of what they saw. The terror rising was for me to be held outside, and I wrongly believed that the glass barrier didn’t permit the transmission of my feelings of deprivation. But my younger brother had scrambled off his chair and pressed his face grotesquely against the window pane, mocking my isolation. He’d read the singular truth that I was set apart, egregious, and he was reacting to it. I read in his gaze that it was I who was the stróinséir, an odd stranger who wasn’t part of the household, the one left over as a remainder. I also experienced for the first time that people could travel from my outside in as if my skin were permeable. Or perhaps it’s because I was born inside-out; it certainly feels that way.

I hope I do my mother justice. I seem destined to fail in the attempt to express what’s been left unsaid between us. My words will be inadequate and partial, merely an approach, an approximation, which may do violence to her. ‘Imagine,’ she has instructed, furnishing me with all the information that’s required. She’s invoking my powers of imagination to supplement her deficiency, but inevitably I’ll fall short. Maybe somewhere she understands that too: that I’ve failed her, inasmuch as she has herself been failed by words, which have run away over the ridges of sand, leaving her lost in the desert. Somehow I’m complicit in that abandonment, and by exploring the something my mother has to say, I shall uncover the truth of my role in her life, and ultimately my transgression.

When I finished writing my memoir At Five in the Afternoon, I understood that what I’d written no longer belonged to me, but to the reader. He brought his own being to the words, and breathed into them a life which was different to what had inspired me. Even though it was recognisably my life story, it brought forth a different book which gave off a smell I didn’t recognise. A reader from Kinsale sent me an email containing a Jehovah-like denunciation: ‘You have shamed yourself, your family, your friends and colleagues in the manner you portrayed them.’ That was taking my text and stretching it out, leaning forward with it, an effort that I hadn’t made. The wording of what I’d written was an obstacle to the flow of his being that obviously lent itself to such an interweaving, but I felt that the resulting garment didn’t fit out my soul, while it thoroughly went along with someone else’s. I’d been displaced from my mooring, which made it doubly difficult to feel certain of the truth.

If my mother gets to make her statement in my hearing, I wonder will I be able to accept it willingly, without straining to make it fit into my reality? I was genuinely at a loss as to how to reply to that reader’s words, because he spoke in a different language, and sought to discredit my experience of abuse: ‘In fairness, the only character who comes out well is your partner Terry, who has a real – not imagined – situation to take from his early life.’ What I have learned from living with Terry, and from many years studying psychoanalysis, the obligation to hand back abuse to the perpetrator no matter from whence it came, eventually dictated my response, although it left an after-taste of intolerance. And did the scolding over shaming reveal a truth I couldn’t accept, that his characterisation was a darker mirror-image of myself, an alien that I didn’t want to know lest I be forced to make room inside for an awkward, unmanageable stranger, and have to welcome him back

home as my brother?

Paradoxically, the publisher’s word ‘sooth’ aligns me with the previous generations back through my mother and father. In the time of my ancestors, what is true derived from being. So were I to bypass the disjunction and describe myself as a soothsayer, the particular truth I’d tell would necessarily draw from that universal and ancient wellspring. I admire the wisdom in the way that the word has been constructed and handed on down to me in an eternal relay, but still I feel dislocated. When I read my own book myself, which details my slow recovery from prostate cancer, I’m unable to resume possession of the land, because the enclave of my being inscribed in the book belongs to a different time with a different set of circumstances, and I have moved on. My mother suffers from dementia, which is a chronic deterioration caused by organic brain disease, so that when eventually she speaks her truth, it will have to articulate in distinct syllables a being that we share now in the present, without referencing the past. And consolingly, either of us can attempt to say what we hold in common.

As a writer, I see what is true flicker about in the words and the phrases as I set them down. It surprised me to discover that truth is like a fóidín mearaí, a sod of confusion, on which you can easily lose your step and be led astray. Truth surfaces briefly in the gulf between what has happened for me in the past, and what has not happened to me yet. And the continuous flow of my words onto the page as I type in this no-man’s land names for me a coming-to-be in language that approximates to the truth. I wouldn’t say that the full truth is in the brutal reality of my existence which has been scored onto paper by the printer. Rather, it’s the rising into the air of my spirit, which is momentarily visible in the words on my computer screen, always open to change at the flick of a flying finger, where it produces the music of poetry, as in mythical times the wind would pass lightly over the strings of an Aeolian harp to produce a deep musical chord, rising and falling with the breath of air.

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees The Yankee Club

The Yankee Club The Kingdom of Shivas Irons

The Kingdom of Shivas Irons Wings in the Dark

Wings in the Dark The Big Brush-off

The Big Brush-off Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits

Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits Jacob Atabet

Jacob Atabet Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction

Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction A Night at the Ariston Baths

A Night at the Ariston Baths The House of Pure Being

The House of Pure Being End to Ordinary History

End to Ordinary History Golf in the Kingdom

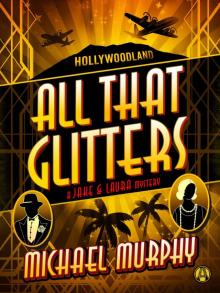

Golf in the Kingdom All That Glitters

All That Glitters