- Home

- Michael Murphy

Golf in the Kingdom

Golf in the Kingdom Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

BE THE FIRST TO KNOW ABOUT

FREE AND DISCOUNTED EBOOKS

NEW DEALS HATCH EVERY DAY!

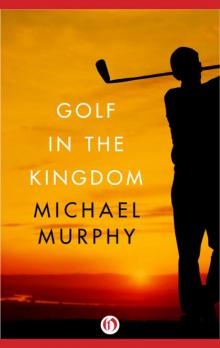

Golf in the Kingdom

Michael Murphy

Hell,” from The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch. Shivas Irons claimed that Bosch played an early form of golf called kolven. This painting, he said, depicts the agonies the painter saw on those early golf courses.

For my parents,

John and Marie Murphy

Contents

PART ONE: SHIVAS IRONS

A Footnote Regarding His Name

GOLF IN THE KINGDOM

SINGING THE PRAISES OF GOLF

SEAMUS MACDUFF’S BAFFING SPOON

WE ARE ALL KITES IN THAT WIND

EPILOGUE

PART TWO: THE GAME’S HIDDEN BUT ACCESSIBLE MEANING

Golf as a Journey

The Whiteness of the Ball

The Mystery of the Hole

Replacing the Divot

A Game for the Multiple Amphibian

Of a Golf Shot on the Moon

THE INNER BODY

A. As Experience

B. As Fact

C. As Luminous Body

SOME NOTES ON TRUE GRAVITY

OCCULT BACKLASH

A GOLFER’S ZODIAC

HOGAN AND FLECK IN THE 1955 U.S. OPEN

A HAMARTIOLOGY OF GOLF

How the Swing Reflects the Soul

THE RULES OF THE GAME (AND HOW THEY ARE RELATED TO FAIRY DUST)

ON KEEPING SCORE

(How Shivas Irons helped the British Empire dwindle)

THE PLEASURES OF PRACTICE

Keeping Your Inner Eye on the Ball

Blending

Becoming One Sense Organ

The Value of Negative Thoughts

(Turning the evil urge toward God)

On Breakthroughs

(The greatest breakthrough is taking forever)

Against Our Ever Gettting Better

The Game Is Meant for Walkin’

Visualizing the Ball’s Flight: How Images Become Irresistible Paths

SHIVAS IRONS’ HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD

(With some predictions regarding full flight in true gravity, the luminous body, knowledge of the cracks in space-time, and universal transparency)

THE CROOKED GOLDEN RIVER

A List of People Who Knew Knew

THE HIGHER SELF

RELATIVITY AND THE FERTILE VOID

UNIVERSAL TRANSPARENCY AND A SOLID PLACE TO SWING FROM

HUMANS HAVE TWO SIDES, OR DUALISM IS ALL RIGHT

(The psychology of left and right, the myth of the fall, and the need to collapse)

HIS IDEAL

(The twentieth century is a koan, but that is a very good thing; from a chameleon on a tartan plaid to life in the contemplative one)

THE DANCE OF SHIVA

AFTERWORD: SPRING 1997, THE SUBLIME AND UNCANNY IN GOLF

Reflections on the Rules of Golf

A BIOGRAPHY OF MICHAEL MURPHY: A BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR THE RECONSTRUCTED GOLFER

THE SHIVAS IRONS SOCIETY

“The game was invented a billion years ago–

don’t you remember?”

—Old Scottish golf saying

PART ONE

Shivas Irons

IN SCOTLAND, BETWEEN THE Firth of Forth and the Firth of Tay, lies the Kingdom of Fife—known to certain lovers of that land simply as “The Kingdom.” There, on the shore of the North Sea, lies a golfing links that shimmers in my memory—an innocent stretch of heather and grassy dunes that cradled the unlikely events which grew into this book. For reasons political and arcane I cannot tell you its real name, so will call it instead the Links of Burningbush. Maybe you have played it yourself and will recognize it from my description. But I must warn you that even its terrain and the name of the town in which it is located are veiled, for the members of the venerable golf club that governs those links are strangely threatened by the story I will tell.

There I met Shivas Irons, introduced to me simply as a golf professional, by accident one day in June 1956. I played a round of golf with him then, joined him in a gathering of friends that evening, followed him into a ravine at midnight looking for his mysterious teacher, watched him go into ecstatic trance as the sun came up, and left for London the following afternoon—just twenty-four hours after we had met—shaken, exalted, my perception of things permanently altered.

The first part of this book is about that incredible day, seen again through fifteen years in which my memory of our meeting passed through unaccountable changes. How did he and his teacher carry on their experiments with consciousness and the structure of space during all those rounds of golf on the Burningbush Links without the players or greenkeepers ever knowing? Did he actually change shape and size as I seem to remember him doing, or was that a result of the traumas I went through then? Did he drive the eighteenth green some 320 yards away? I’m fairly certain he did that. During the years since our meeting I have been haunted by questions like these. Our day together has gotten into my inner life, shaping and reshaping my memories, my attitudes, my perceptions. At times I almost think he is here in the flesh, his presence is so vivid, especially when I play a round of golf. Then I could swear he is striding down the fairways with me, admonishing or consoling me with that resonant Scottish burr or suggesting some subtle readjustment of my swing. His haunting presence leads me back to the game, in spite of all my prejudice against its apparent inanities. On a golf course I can begin to recreate that day in 1956.

Part two of this book is my attempt to make sense of some passages which I was fortunate enough to copy from his journals. For the man was a philosopher-poet and an historian of sorts. His sayings have stuck in my mind as well as the memory of his prodigious golf shots. Whatever led me to copy those sentences escapes me now. Like my meeting with him, I must put it down to unbelievably good luck. Or perhaps I knew, in some precognitive way, that I was not to see him again. For I have tried without success these several years to re-establish contact with him. In the town of Burningbush no one knows where he is or what he is doing. He is simply—as the barman at the ancient golf club said—at large in the world.

When I left Scotland after that memorable visit, I was on my way to India, to study philosophy and practice meditation at the ashram of the Indian seer Aurobindo. When I reached my destination, I became absorbed in the discipline I found there and the memory of my time in Burningbush began to recede. In that austere and devoted place adventures on golf courses seemed a frivolous waste of time. My rhetoric and interior dialogues then were clothed in the words of Aurobindo and Saint John of the Cross, Plotinus and Meister Eckhart. Hardly a notion or phrase from my conversations in Scotland crept in.

After a year and a half in India, I returned to California. It was then that Shivas Irons began to haunt me. I began to hear his voice, making the same suggestions he had made to me during our day together. “Aye one fiedle afore ye e’er swung,” the sentence came like a litany. Sometimes I would hear him as I was falling asleep.

In the summer of 1961 Richard Price, a classmate from Stanford who had become fascinated with the latent possibilities of the mind, heard that I was living in San Francisco and came to see me. Before long we had conceived a plan for an institute in Big Sur, on my family’s old estate there, and our dream soon became a reality of sorts—not the one we had talked about exactly, but something like it, something recognizably in the direction of an ashram and forum where East and West could meet. About that time memories of Shivas took an even stronger hold on me. That someone so mystically gifted should be a golf p

rofessional—and such a proficient one—filled me with increasing wonder. For the difficulties of remembering and embodying the higher life while laboring in the lower were becoming ever more apparent as our little institute took shape. Psychiatrists, hippies, and swingers, learned men from universities and research centers, wounded devoted couples and gurus from the end of the world were descending upon us in answer to our letters and brochures. We were caught in a social movement we hardly knew existed. New adventures of the spirit were beginning, of the spirit and the body, of the spirit and the bedroom, of encounter groups and endless therapies—a vast exploration of what my teacher Aurobindo had called “the vital nature.” Swept along in the heady river of The Human Potential, as we called it then, I came to admire what Shivas Irons had so firmly joined in his life—all those worlds above and below that met in his remarkable golf swing, in the way he greeted friends at the bar of the Burningbush club.

One night in Big Sur, after a particularly rousing and exhausting session of something called “psychological karate,” I was drawn to the box of papers I had collected during my trip to India. I found the notes I had copied from his journals. Seeing them again in Big Sur, so far from the Kingdom of Fife, brought back the experience like a flood. Suddenly the feeling of it all, the smell of heather and those evanescent vistas of purple and green were there again in all their original intensity. For an hour or so I was in Scotland again, walking the cobblestone streets of that little town, smelling the salt air, looking out in some kind of satori from the hill above hole thirteen. The thrill of it was so deep, so full of blazing awareness that I wondered how I had forgotten. I was dumfounded, as I read through those notes, at my genius for repression.

I decided that the time had come to reestablish contact. The next day I wrote him a letter. Months passed without a reply. But my desire to hear from him continued to grow. I wrote a second letter sometime during the summer of 1964, but still there was no reply. I wrote a third to his friends the McNaughtons, but it was returned without a forwarding address. By then it was well into 1965 and I was caught up in the full tide of those Utopian days at our institute. We were becoming famous, at least in certain circles, and for a while it seemed that we were on the verge of some immense discovery. We were planning a Residential Program with a huge array of disciplines for stretching the human potential; the idea behind it was to develop “astronauts of inner space” who would break through to dimensions of consciousness not yet explored by the human race. At times we talked in terms of a “Manhattan Project” of the psyche. But it soon became evident that breakthroughs could be in the wrong direction, that we were in for a longer haul than some of us had thought. Our more ambitious programs began to founder as some of our astronauts came crashing back to earth, and we began to learn that the programing of consciousness was an unpredictable venture. This sobering change in perspective was reinforced by what we saw happening in the Big Sur country around us. Thousands of young people from all over the United States were coming down the coast highway looking for some final Mecca of the counter-culture, and during the summer of 1967, the “Summer of Love,” it seemed that most of them wanted to camp on our grounds. They came with dazed and loving looks, with drugs and fires, swarming into the redwood canyons and up over the great coast ridges, many of them polluting and stealing along the way. The air was filled with a drunken mysticism that undermined every discipline we set for the place. Late that summer I got hepatitis.

Convalescing, I resolved that I would visit Burningbush again and find the man who embodied so much of the life I was aspiring for, so much that was lacking in that summer of chaos. But a slow recovery and the adventures and problems of our institute kept me from the journey for another three years. I was not able to arrange a visit until the summer of 1970.

I had come to England with a group of friends, and as soon as I could I rented a car and drove to Edinburgh, and thence to the Kingdom of Fife. But what disappointment! Shivas was long gone, where he was no one knew. His old landlady rolled back her eyes when I asked about him, gave a wistful shrug, and said that letters sent to his forwarding address in London were now returned. He had left sometime in the fall of 1963. “Oh, he was a wild one,” she said in that fondly reproving way I remembered all his friends doing. I could tell she still missed him terribly.

The Burningbush golf club was rich with the smells of leather and burning logs, with quiet good cheer and mementos of a treasured past—crossed swords and tartans, enormous trophies and pictures of ancient captains staring down from the walls. The bartender, my one link with that day in 1956, fondly reminisced about his extraordinary friend. I learned then that Shivas had never actually worked for the golf club itself. He had been a teaching professional in his own employ; he had wanted it that way to “preserve his peculiar teaching ways.”

“Oh, there was no one else like ’im, that’s for sure “ the barman said and smiled wistfully. “’Cept for Seamus, and he’s gone, too.” Seamus MacDuff, whom Shivas called his teacher, had died a few years before. So had Julian Laing, the town’s remarkable doctor who was another of Shivas’s special friends. Evan Tyree, the well-known golf champion and his most famous pupil, had gone to New Zealand in some mysterious land deal. And the McNaughton family had moved to Africa. All the people I had met fourteen years before had vanished, except for this good-natured rotund barman, red-faced and grayer than when I had seen him last.

I introduced myself, suddenly aware of how important he was, my last link with Shivas Irons conceivably.

“Liston’s my name,” he said, reaching out a hand, “just call me Liston. Christian name’s Sonny, but the men here call me Liston.” He slipped me a glass of Scotch—and then another—and we spent the afternoon reminiscing about our departed friend while he served the club members and kept the fire, which I remembered so well, burning brightly.

“It was amazin’ to watch him come on to the people here,” he said, “he was so different with each and every one, if ye watched him close. So I can see wha’ ye mean when ye say he changed his shape. I watched him for so many years, watched him grow up, ye know. He was more fascinatin’ the more ye watched him. My wife used to say she could tell when we’d been togither—said I picked up his way o’ talkin’ and gesturin’. Funny thing about that, she liked it when I’d been around ’im, said I seemed to like her more afterwards.” He shook his head with the knowing smile of a husband who has been through the marital wars. “He was a vivid one awright. Ye know another peculiar thing? I’ve been thinkin’ about ’im lately, been thinkin’ o’ the way he hit his practice shots out there,” he pointed out a window to a deserted tee. “There was somethin’ about the way he hit those shots tha’ used to get to me—and still does—somethin’ funny. I still think about that swing o’ his . . . and the look on his face.” I asked him if he and Shivas ever talked about the philosophical side of the game. “Very seldom,” he said, “hardly ever, come to think of it. I never understood his talk about the inner mind and such, but he never talked much like tha’, just now and then wi’ someone like yersel’, someone on to philosophical things. But with everyone he talked—never knew ’im to be lost for words. Course most o’ the men here wanted his advice from time to time, and he was quick to give it.”

I asked him if he had any idea about where Shivas might be. “No idea at all,” he said. “Somethin’ was gettin’ to him though, toward the end. He talked a lot about the need to move on, heard him say that to the people here before he left. Sometimes too he talked about his needin’ to help the poor.” He shook his head as if he were puzzled. “And then there was quite a bit o’ talk about his galavantin’. ’Twas said he had some problems wi’ the women. ’Twas even said he was a little off when it came to the ladies.” He pointed a finger at his head as he said this. “But of coorse ’twas said about him generally from time tae time—just a little off.” Again the finger was pointed at the head. “But he was aye guid to me, and a great one for singin’ and enjoyin’.

No one else could sing a ballad like ’im.”

After more conversation, it became apparent that Liston still missed his friend keenly, and was telling the truth when he said Shivas had left no traces. No one in Burningbush, it seemed, knew how I could find him.

I left Scotland in a heavy depression. I had waited so long to see him again, a place in my consciousness had been prepared for our eventual meeting. The depression lasted until I decided to write this book. Writing it would summon his presence, I thought, and indeed it has. Digging into my memory for clues to his character and state of mind has yielded unexpected insights. Once I began to write, I realized that that one day in 1956 had enough in it to last me a lifetime, especially if I put some of his admonitions to work.

Having completed this book, I realize there was far more to Shivas Irons than I have been able to capture. Some of his enigmatic remarks, all those journals of his I never opened, and the unexplained events of that day in 1956 constantly remind me of that. There is much about our meeting that is still obscure. I have decided to put forth what I have, however, rather than wait for the day of final clarity, which may yet be a long way off.

And also—I must admit it—a hope lurks that this slender volume will lure its real author out of hiding.

A FOOTNOTE REGARDING HIS NAME

As I have said, “Burningbush” is a fanciful name for the actual golfing links in Fife upon which my adventures took place. The same is true for the names of three or four characters in the story. But I have left the name of my protagonist intact: Shivas Irons was the appellation he had carried all his life. It is so unusual that I have looked up its etymology; and indeed there are records of its origins and history. Shivas or Shives is a Scottish family name, which was known in East Aberdeenshire as early as the fourteenth century; a district there has sometimes been known as Shivas. Chivas Regal is a famous Scotch whisky. In Scots dialect there is a verb “shiv” or “shive,” which means to push or shove; perhaps the family took its name from some early conquest in which it pushed the older peoples out. There is also a noun “shive,” which means a slice of bread; I would prefer to think that his name derived from that, since he offered me the very bread of life in his presence and wisdom. There is also the noun “shivereens,” which has approximately the same meaning as the word “smithereens,” namely fragments, atoms, shivers (“he was blown to smithereens”); that relationship is apropos, seeing what he did to certain people’s perceptions. I could find no connection though with the ancient Hindu name for the God of Destruction and Redemption, perhaps the oldest of all living words for Deity (icons of Shiva date back to the second or possibly the third millennium B.C.). That was a disappointment, but I have consoled myself by remembering that direct etymologies are not the only sign of inner connection.

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees The Yankee Club

The Yankee Club The Kingdom of Shivas Irons

The Kingdom of Shivas Irons Wings in the Dark

Wings in the Dark The Big Brush-off

The Big Brush-off Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits

Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits Jacob Atabet

Jacob Atabet Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction

Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction A Night at the Ariston Baths

A Night at the Ariston Baths The House of Pure Being

The House of Pure Being End to Ordinary History

End to Ordinary History Golf in the Kingdom

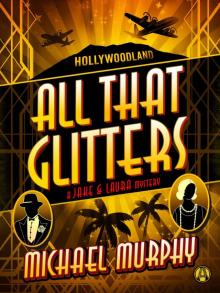

Golf in the Kingdom All That Glitters

All That Glitters