- Home

- Michael Murphy

Golf in the Kingdom Page 2

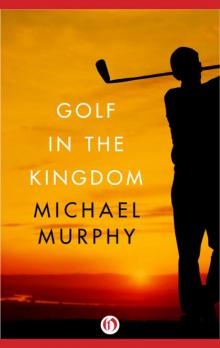

Golf in the Kingdom Read online

Page 2

The name “Irons” was known in the region of Angus as early as the fifteenth century. I have not been able to trace a clan connection for it, however (or for Shivas). Every bit of knowledge regarding his ancestry holds great fascination, I find, increasingly so as my hopes of seeing him again continue to fade, for perhaps the family history will give me some clue to his character. The Scots word “iron” (or “irne”) is interesting in this regard, for it means a sword. That it came to mean a golf club suggests an important turn in the Scottish character. Indeed, it also came to mean a part of the plow. Turning swords to plowshares is, as I like to see it, one of the chief promises the game holds out for us.

Shivas Irons: it is such an appropriate name for the man. What did his parents have in mind when they laid it on him? Another Scottish philosopher, Thomas Carlyle, said a name surrounds us all our life like a cloak and “. . . what mystic influence does it not send inwards, even to the centre; especially in those plastic first-times, when the whole soul is yet infantine, soft, and the invisible seedgrain will grow to be an all overshadowing tree!” A name can shape a life, and if his soul took birth to do the work I found him doing, how well his parents sensed it and named him for the task.

Golf in the Kingdom

PERSONAL CHARM IS A physical thing. It also carries elements of endless surprise. Physical and surprising, matter and something new, bodying forth what you would never expect. From the very beginning that is what my encounter with Shi-vas Irons was like.

The pro shop at Burningbush stands behind the first tee, some 30 yards from the imposing clubhouse. The little building seemed familiar as I entered, for I had read about it in a book of memoirs by a famous Scots golf professional. There was even a sense of déjà vu as I looked around the place; I could have sworn I had seen the little man behind the starter’s desk before. He showed me the clubs and shoes he had to rent, studying me, as he did, with a sly curiosity. I could tell he was watching as I waggled some of the woods and irons.

“Are ye lookin’ for a game?” he asked. I said that I was. Having heard so much about the difficulties of Burningbush Links and its well-known obstacles, I felt I could use some support and guidance going around it.

“Are ye an American?” he asked as he fussed with his equipment display.

“Yes, I am.”

“A toorist heer?”

“I’m a student. I’ve heard a lot about Burningbush and always wanted to play it. I had a dream once I played it.”

“Wha’ ye studyin’?”

“Philosophy. I’m on my way to India.”

He watched me put on a pair of golf shoes and choose the set of clubs I wanted.

“Well, I think I can get ye a game,” he said after a moment’s silence. “There’s a professional here takin’ someone for a teachin’ round. Maybe ye’d like to play along wi’ them?”

I was delighted. A pro could help me out there on Lucifer’s Rug, I said, referring to one of the links’ famous hazards.

“Oh, he may help ye now, and then again he may na’. There they are, out there.” He pointed through the pro shop window to a pair of men talking on the first tee.

I gathered up the paraphernalia I had rented and carried it outside to a little bench, then took out the driver for some practice swings. The two figures were conversing about 30 feet away. They stood with their backs to me, looking down the first fairway. The taller of the two, obviously the teacher, was pointing to a distant object and explaining something with a voice that conveyed a strong sense of authority. I walked toward them and hesitantly cleared my throat. But they continued talking, apparently unaware that I was there. I cleared my throat again and ventured a small “Hello.” The taller one, the teacher, turned to face me. That penetrating, disconcerting look—I realized at once that we had already met!

About an hour before, I had taken a wrong turn on my way to the clubhouse. By mistake I had gone down a path behind the caddies’ shelter and had come to a dark, narrow corridor between the shelter and a high embankment. About 15 feet away from me, a figure was jumping grotesquely and kicking at an overhanging beam some 10 feet above the ground. With each kick the jumping figure would twist and fall back, breaking the fall with outstretched arms. The performance was repeated several times. He was apparently trying to kick the beam, trying to reach a point as high as a basketball hoop with his foot instead of his hand! Not knowing whether to intrude or retreat, I stood transfixed in the shadows of the passageway as this strange performance continued. The only sound the jumper made was a weightlifter’s explosive exhalation before each effort. He was totally unaware of my presence. After five or six arabesques in midair, he finally grazed the beam above him with the toe of his shoe—I realized it was a golf shoe!—and landed on his chest and stomach. For a moment he lay with his face to the ground, breathing deeply. Then he looked up and saw me staring down at him with embarrassed fascination.

He stood up without a word, pulling himself to his full height, some six feet two or three, and I met that uncanny look for the first time. It was ever so slightly cross-eyed—perhaps from the jumping—something wild and serene, for a second the space between us wavered.

Then, suddenly, he grinned and a second face appeared, an entirely different emanation, a look that was immensely warm and engaging with a big, slightly bucktoothed grin. He winked and wagged his head with an ironic gleam—as if to say, “Hang in there, boy”—and walked past me without a word. As he went past, I could smell him. It was the smell of eucalyptus and baking bread, a powerful and distinctive odor.

Now here we were face to face again. A shock of untamed reddish hair fell across his forehead and his blue unsettling eyes looked straight into mine. I introduced myself. He smiled his bucktoothed smile again and said in his resonant Scots dialect, “Shivas Irons ma nemme, and this gentleman is Mr. Balie MacIver.” He pointed to his playing partner, then turned abruptly to look down the fairway. I brought my golf clubs up to the tee blocks and took a few practice swings, relieved that he was preoccupied with the lesson he was giving.

While I practiced swinging, I watched them. It was hard to follow their Scottish idiom, but I got an idea that he was giving MacIver a kind of game plan for the entire round. “Noo, we’ll play six holes for the centered swing, six tae feel gravity, and six tae scoor,” he said—or something to that effect. Then they stood for a moment with their eyes closed, as if they were praying. Maybe they were saying the Lord’s Prayer, I thought, like professional football teams do before a game.

After their brief meditation they started taking their practice swings. MacIver took his with a long iron. “Nae. Use yer play club noo,” said the professional, pointing to his pupil’s driver. As I would learn eventually, he believed that “driving” was a term that by its very connotation threw some golfers off their truest swing. He preferred to say that he was “playing” the ball on a drive, and called a driver a “play club,” as golfers had done in centuries past.

As I watched him I could see he was not your ordinary golf professional. His look was an important part of his teaching. To emphasize a point he would impale MacIver with it, then flash his big engaging smile when a point had been conveyed. As I moved closer I saw that his left eye was slightly off focus—not enough to be readily perceptible, but enough to be disconcerting. It was focused ever so slightly to the center, giving his steady blue eyes a penetrating quality, almost as if he were looking at you from two vantage points at once. “Murphy,” he said turning to me, “ye swing at the grass real purty, hav’ a try at the ball”—a challenging invitation. He smiled as he said it and gestured toward the tee.

As I teed up my ball I looked down the gently rolling fairway. It was serenely inviting in the afternoon sun, but I knew from my reading that hazards lurked along its course all the way to the green. I could hear the pounding of ocean waves beyond the rough and see them breaking over boulders within range of an errant drive. The anticipation of playing Burningbush and this unusual golf pr

ofessional’s commanding presence had thrown me off—I remember wishing we could stop to pray again. As I addressed the ball I knocked it off the tee with the club face. Shivas Irons seemed to be seven feet tall as I glanced back. He looked down at me with compassionate good humor, as if he were rooting me on. He made one small gesture, a brief movement of his hand in front of his hips, palm held downward. I instantly knew what he meant. As I teed the ball up again I settled into a feeling of stomach and hips, making a center there for my swing. And then a vivid image appeared in my mind’s eye, of a turquoise ball traveling down the right side of the fairway with a tail hook toward the green. I took my stance and waggled the club carefully, aware that the image of the shot was incredibly vivid. Then I swung and the ball followed the path laid down in my mind.

“Guid shot,” he said loudly, “ha’ did ye ken tae hit it thair? ’Tis the best lie tae the green.”

“Just luck,” I mumbled and stood aside, relieved that I had gotten past the first obstacles so well.

MacIver swung with what seemed to be a mere half-effort and his drive traveled 180 yards or so down the middle of the fairway. “That’s it, that’s it,” the professional’s voice rumbled with its heavy brogue. MacIver was dressed in white shoes and pants and a black cardigan sweater. It was a striking costume, all the more so because he seemed so modest. He was completely devoted to his teacher’s admonitions, listening carefully to every word of instruction, concentrating utterly upon the game. He muttered something and stepped aside, smiling proudly in spite of himself.

It was the professional’s turn now. He stooped down gracefully to tee his ball, balancing for a moment on one leg as if to test his balance and spring. It was a kind of ritual dance he was to repeat on several holes. Then he stood addressing the ball for a few seconds, a brief address, but during that moment all his attention came to awesome focus. Like Ben Hogan, he seemed to peer into the very center of the ball and summon a secret strength. I could feel the energy gathering, feel it in my solar plexus, a powerful magnetic field drawing everything into itself—and then his swing unfurled, slower than I had anticipated after that awesome address but impacting with immense power and following through with utter grace and balance. I held my breath as the ball flew, stretching as if to hold it in the sky. It sailed 280 yards or more down the middle of the fairway—hovering there longer than any shot I had ever seen—then it landed, bouncing high toward the green. He picked up his tee, winked, and gave a little kick to suggest the performance I had watched behind the clubhouse. “Someday perhaps the ba’ will na’ come down again,” he said with a smile. “Have ye e’er had tha’ feelin’?” He was obviously pleased. It had been an awesome shot.

He walked ahead of us down the fairway with a long rhythmic stride, a russet sweater tapering from broad shoulders to a pair of hips as well formed and contoured as a football player’s. He wore a pair of golden-brown corduroy pants and ordinary brown golf shoes. I found it hard to take my eyes off him. He stopped by MacIver’s ball and watched his pupil make the next shot, another half-effort that landed in front of the green.

By now MacIver was totally preoccupied with his game. His swing was neither graceful nor powerful, but it was impressive to see his concentration and total devotion to the discipline his teacher had set for him. I felt a twinge of envy for their collusion.

I hit a seven iron onto the green—the example they were setting was having its effect. Shivas hit a wedge 3 feet from the cup, with the same grace and power he had shown with his drive. I was beginning to feel a sense of awe as I watched him, something I have always felt around consummate athletes. He birdied, I parred, MacIver bogeyed the hole. I wrote a four on my scorecard; MacIver was keeping score for them.

“Ah like yer swing, Michael,” he said as we walked to the second tee, giving me that sudden smile. The remark startled me. I was touched that he called me Michael, that he had noticed my shot.

“Any chance of getting a lesson?” I answered, blurting out the thought that was running through my mind.

He looked directly into my eyes. “Oh, but ye may na’ ken tha’ that is a solemn and serious matter, a serious matter indeed.” He smiled good-naturedly, but I could see that he meant it. Then he grinned and reached out to shake my hand. “Just call me Shivas,” he said.

“Do you teach here all summer?”

“It depends,” he replied, then turned away without further explanation.

The second green could be seen from the tee, some 353 yards away according to the scorecard, down a straight, gently rolling fairway. The rough on the right was full of stones and gorse, or “whin” as it is sometimes called, the small spiny bush that grows on Scottish links-land. An incoming fairway ran down the left side. Not a very difficult hole, I said to myself as I surveyed it. MacIver hit another short, unpretentious shot down the middle, conscientiously following the game plan. It was my turn now. Once again an image came of the ball in flight—a turquoise ball down the middle—and so it flew. I had somehow developed the knack of seeing the shot in my mind’s eye as I addressed the ball. On both drives it had appeared spontaneously, a bright, compelling image. Was I learning something just being around them? Shivas was next. Again the ritual dance as he teed the ball, and again the awesomely concentrated address. He split the fairway with a lower drive this time, something more like a rifle shot. As I was to learn later, he never used the same swing twice—or so he said—though it was difficult for me to see the changes.

As we walked up the fairway, I took the scorecard out and looked at the yardage figures. The course was about 6800 yards long, not too long to play in par. To shoot a par round at Burningbush, that would be something to remember! I began calculating how many birdies I would need, maybe two or three on the par fives, maybe one or two more on the other holes, that would give me a chance for a 72 or better with the bogies I was bound to make. I hurried my steps to see what kind of lie I had for my second shot. The ball was near the center of the fairway, about an eight-iron shot from the green. Maybe I could get a birdie on this one, I thought. Then images of veering shots started to form in my mind. Images of the gorse, of the bunkers in front of the green, of the rocks behind it. I began adjusting my swing as I addressed the ball. The poise I had felt on the drive had disappeared; excitement, anticipation, and bobbing images of disaster had taken its place. I backed away, and approached the ball again—and then as I began to swing, a picture came of the gorse to the right. I pulled the shot to the left, into the adjoining fairway. I slammed the club into the bag and hurried toward my ball, not waiting for the others.

“Now, hold there, Michael,” Shivas’s authoritative voice came booming across the fairway. “Just wait yer toorn.” He was suddenly stern as he looked at me.

I stopped in mid-stride and waited for them to play. As I stood watching Shivas make his shot—another lovely approach onto the green—my fantasies of an exceptional score continued. I pulled out the scorecard again to see which holes were par fives.

When I got to the ball, I saw that a bunker stood between it and the green. The pin was about 100 feet away, just a pitch and run for a par. I pulled a nine iron from my bag and took a few practice swings, adjusting them for distance and roll. With each practice swing the bunker got larger. I backed away twice from the halibut to no avail. As I swung, I looked up and the ball landed in the sand. I lifted back my head and stared up at the sky, hovering somewhere between a curse and a prayer. Shivas and MacIver watched in silence. As I disappeared into the bunker they waved and shouted some words of encouragement, but that was the only sound until I blasted onto the green and two-putted for a double bogey. My fantasies of a 72 at Burningbush had been dealt a blow.

A little bench stood behind the third tee. MacIver sat down on it and began writing scores on his card. To my surprise he wanted to know what I had shot on the two holes we had played. “I’ll keep my own score,” I said. “You have your lesson. Don’t bother.” I didn’t want to say it out loud, that I had

shot a six. We all knew, but saying it out loud was harder. But MacIver insisted that he keep all our scores. “Four on the first, and a six on the second,” I finally said. “That damn bunker, and I should have sunk the putt. . . .”

“Ye had a five oon the first,” Shivas interrupted me sternly.

I turned to face him. He was looking straight at me, with that steady cross-eyed gaze. “Ye must count that one ye knocked off the tee when ye took yer waggle,” he said solemnly.

Have you ever felt as you talked to someone that everything was turning unreal? That is exactly how I felt then, as I realized what he was saying. The shock of this all-seeing scrutiny, the small-mindedness of it, and the embarrassment I felt for violating their code of honor drew the blood to my stomach.

“So, a five and a six?” MacIver asked.

Shivas could see I was having a hard time answering. “Now, Michael,” he said, raising a long finger and shaking it at me, “ye must rimember that ye’re in the land where all these rools were invented. ’Tis the only way ye can play in the kingdom.” Then the big grin appeared, his second face. I can’t remember what I said in reply, but I submitted to the discipline.

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees

Little Squirrels Can Climb Tall Trees The Yankee Club

The Yankee Club The Kingdom of Shivas Irons

The Kingdom of Shivas Irons Wings in the Dark

Wings in the Dark The Big Brush-off

The Big Brush-off Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits

Dreamspinner Press Year Nine Greatest Hits Jacob Atabet

Jacob Atabet Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction

Jacob Atabet: A Speculative Fiction A Night at the Ariston Baths

A Night at the Ariston Baths The House of Pure Being

The House of Pure Being End to Ordinary History

End to Ordinary History Golf in the Kingdom

Golf in the Kingdom All That Glitters

All That Glitters